Hollywood’s Response to the Hart Kidnapping and Lynching, Part One: Fury

- Feb 14, 2024

- 3 min read

Fritz Lang’s 1936 Fury opens in Chicago when Joe Wilson, an ordinary working man, and his fiancé Katherine must separate for months until they can save enough money to get married.

Joe goes back and lives with his two brothers in a Midwestern small town who, given the harsh economic reality of the Depression, are engaged in petty crime. Joe denounces his brothers’ crooked lifestyle and in time saves his money, buys a gas station and convinces his brothers to join him at his business.

At last, Joe arranges to meet Katherine so they can marry. Along the way outside a small town, Joe is pulled over by a hick policeman and drags him to the local sheriff who mistakenly identifies him as the one behind a prominent kidnapping. Joe is thrown in jail.

Holding him on flimsy evidence, news of the capture of the alleged kidnapper ignites the town’s rage. The pious, small-town people are transformed into a mob bent on vengeance.

When the sheriff requests reinforcements to protect the prisoner, the governor refuses because public sentiment approves his crack down on criminality. Despite using tear gas, local police are overwhelmed by the mob.

They attack the police, use a battering ram to knock down the doors to the jail, but are prevented from dislodging Joe from his cell.

In a rage, the mob sets the jail on fire, prevents firemen to extinguish the flames while the police watch helplessly. Katherine arrives at the scene, witnesses the mob defy local authority, and sees Joe about to be burnt alive. Someone throws in sticks of dynamite. There is an explosion and Joe is presumed dead.

But, Joe manages to escape. Presumed dead, he plans to take revenge on the would-be lynchers declaring, “I’ll give them a chance that they didn’t give me. They will get a legal trial in a legal courtroom. They will have a legal judge and a legal defense. They will get a legal sentence and a legal death.”

The district attorney identifies twenty-two citizens and charges them with Joe’s murder.

Fixated on vengeance, Joe becomes spiritually dead. His survival is only known to his brothers.

The brothers visit a traumatic Katherine who is emotionally scarred from the ordeal.

During the trial Joe hungrily listens to the trial on radio. All the defendants have alibis collaborated from townspeople insisting that they were nowhere near the jail, but a film crew later proves their participation.

Joe is flummoxed when the defense attorney declares that without proof of Joe’s death, there is no crime and asks the judge to dismiss all charges.

Joe manufactures evidence that forces traumatized Katherine as a key witness to testify that a newly recovered engagement ring belonged to Joe providing admissible proof that he has succumbed in the jail.

Upon a guilty verdict of several of the defendants, Joe, having undergone a personal transformation, appears in the court proceedings and confesses what he has done. He reveals to the judge that “…..the law doesn’t know that a lot of things that were very important to me, silly things maybe, like a belief in justice, and an idea that men were civilized, and a feeling of pride that this country of mine was different from all others….”

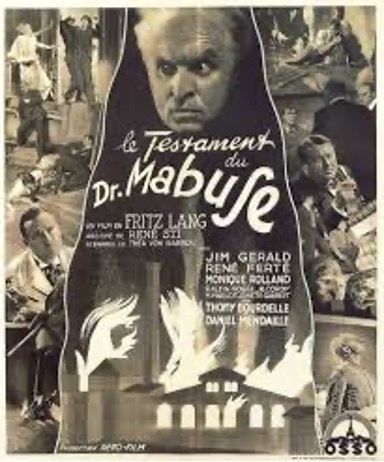

Fury evokes many of Fritz Lang’s entire spectrum of themes throughout his directorial career: mass hysteria, injustice, corruption and paranoia. Lang’s last German film, the 1933 The Testament of Dr. Mabuse was a horrifying vision of a submissive society held under the spell of a charismatic authoritarian. Nazi Joseph Goebbels was so intrigued by the film’s message that he offered Lang to become the head of the German film industry. Lang fled the country.

In his first American film, Fury begins with the belief that if Joe plays by the rules, works hard, he will succeed. However, Lang as an escapee from Nazi Germany twists this dream. He warns his audience that even this small-town symbol of Americana could turn into a nightmare when seduced townspeople subvert constitutional rights in exchange for mob rule. The New York Times called Fury “a mature, sober and penetrating investigation of a national blight…Its theme is mob violence, its approach is coldly judicial, its treatment as relentless and unsparing as the lynching it portrays.” Fritz Lang uses the Brooke Hart lynching as a warning of people’s gullibility and manipulation that mirrored the Nazi rise to power.

Comments